Nicolas Hayek died the way he probably wanted to, enjoying his daily leisure time at his desk in Biel. He was a grand entrepreneur in a class of his own. If anything came close to the art of business, it was what he did, and like all great artists, whatever he did seemed easy. Of course he could toot his publicity horn as much as anyone – did I say horn? I meant a five-manual organ – but that is the business of truly loving your business. Furthermore, his grandson, Mark Hayek, once told me in an interview that his grandpa relaxed on Sundays by doing the books. His concern for his industries and the people working for him was genuine, and that is what made him one of Switzerland’s most trusted public figures. When he said “sustainability,” it was not just fig leaf stuff, it meant something, because he believed in it. Swatch Group managed to navigate the massive recession of 2008-2009 without shedding many jobs. That must have given Nicolas Hayek a feeling of success, if not elation.

As a journalist, one who keeps a very low profile, I was thrilled to be able to write about Nicolas Hayek following an interview he granted me at the Baselworld 2008 watch fair. I wanted to discuss his project for a solar-powered fuel-cell car. I was given a 20-minute slot and stayed 45. Within that short time span we covered all sorts of subjects, from his Marie-Antoinette watch, to green technology, passing by the Middle East. There are several statements he made that I have never forgotten, in particular his attributing success in business to a CEO’s ability to motivate workers. Ironically, at around the same time, I – who knows Pittsfield, MA, and the social and environmental disaster area left behind by GE in what was their company town – was asked to go to a press conference given by Jack Welch and write about Neutron Jack (the article appeared under the title Jurassic Jack). It was like listening to a Mahler’s 8th Symphony and following it up by chopsticks played at supersonic speed.

So without further ado …. Nicolas Hayek as I humbly saw him.

If an adult male would walk around saying he believes in Santa Claus, he would probably end up spending some time under observation at the nearest booby hatch. Or receiving medication, as befits our zeitgeist. But when Nicolas Hayek said so, ears pricked up, eyes lost their glaze, brains fine-tuned their reception mode. Not because anyone thinks that he really believes in some fellow with a beard and dressed in a red cloak distributing presents from a sled pulled by reindeers. Rather, Hayek, founder of Hayek Engineering, co-founder of Swatch Group and the impulse behind Smartcars, is revealing one of the secrets of his success as an entrepreneur.

The first impression – usually correct – is one of complete authenticity: He sits at a utilitarian table cluttered with a few cups, a bottle of water, a few glasses, a notebook (the paper type with little squares on it), the flotsam and jetsam of myriad meetings, a wireless phone that never seems to ring, and a plate filled with dried fruit and nuts. “An entrepreneur is not a businessman, not a manager, not a Harvard Business School MBA,” he insists. “An entrepreneur is an artist who has kept the fantasies he had when he was six years old. I believe that everybody who is healthy was a very creative, imaginative person when he or she was 5, 6, 7, 8. Then society, schools, university, military service… all that kills your creativity.”

Nicolas Hayek, born in distant Lebanon in 1928, never lost that childlike fire. He mentions some books of the great writers, Lamartine, de Musset and Victor Hugo, that he keeps in his Biel office and underlines the fact that among them are copies of Donald Duck, for him the wellspring of fantasy. “You must believe in miracles and to do this,” he adds, “you must be immune to society’s pressures telling you things are not p ossible.”

ossible.”

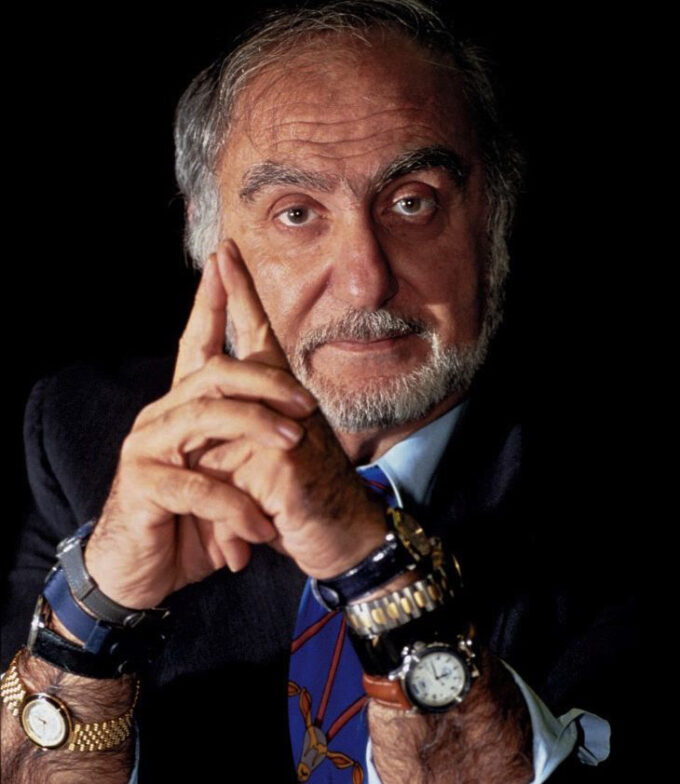

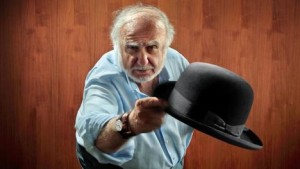

Looking at this man, with his scruffy beard, his trademark multiple watches and his engaging smile, it is not hard to see the impish character lurking in the shadows. He has somehow nurtured, fed, protected and entertained the little boy named Nicolas Hayek for eight decades, he has carried that boy across rough seas, through hard times, stressful times, perhaps, countless board meetings, executive decisions, without ever losing his sense of playfulness. It is not surprising to hear him repeat what he told one journalist years ago when asked how many hours does he work per day: “Not a single minute.”

Just do it

So his world, his empire, as he willingly calls it, has been built over time by simply accepting challenges and turning them into a game. “The only thing you cannot overcome is death and taxes,” he works in the old joke, making it sound fresh somehow. “Every time people told me something was impossible, I did it. Including this thing here.” He points to a large, delicately crafted wooden box of light oak decorated with an almost ethereal weave pattern.“This thing” is the repository of one of Hayek’s grand pet projects, launched in 2005, the replica of the famous Marie- Antoinette pocket watch. To reach it, secret buttons must be pressed in the box’s side – the object was built by Swiss craftsmen, Hayek points out with a teacher’s raised finger; it consists of 3,000 pieces of wood. The top opens to reveal a dial and an excerpt of one of the LeBrun’s portraits of Marie- Antoinette. It features a single rose. Another secret button is depressed, the rose rises, and there lies Breguet’s contemporary horological treasure.

People come and go during the interview, the visitors’ dress code is in sharp contrast with Hayek’s casual appearance. The men wear dapper suits, pants with razor-sharp creases, styled hair, buzz cuts, gold watches, of course. Women are simply chic to no end. This is Baselworld, after all. The mood is fairly relaxed thanks to Hayek’s jocular tone. Each time the door opens, he stands up and shows the “Marie-Antoinette” with visible glee. His enthusiasm is infectious; it breaks through the formality and overwhelms the somewhat inhibiting awe of the moment.

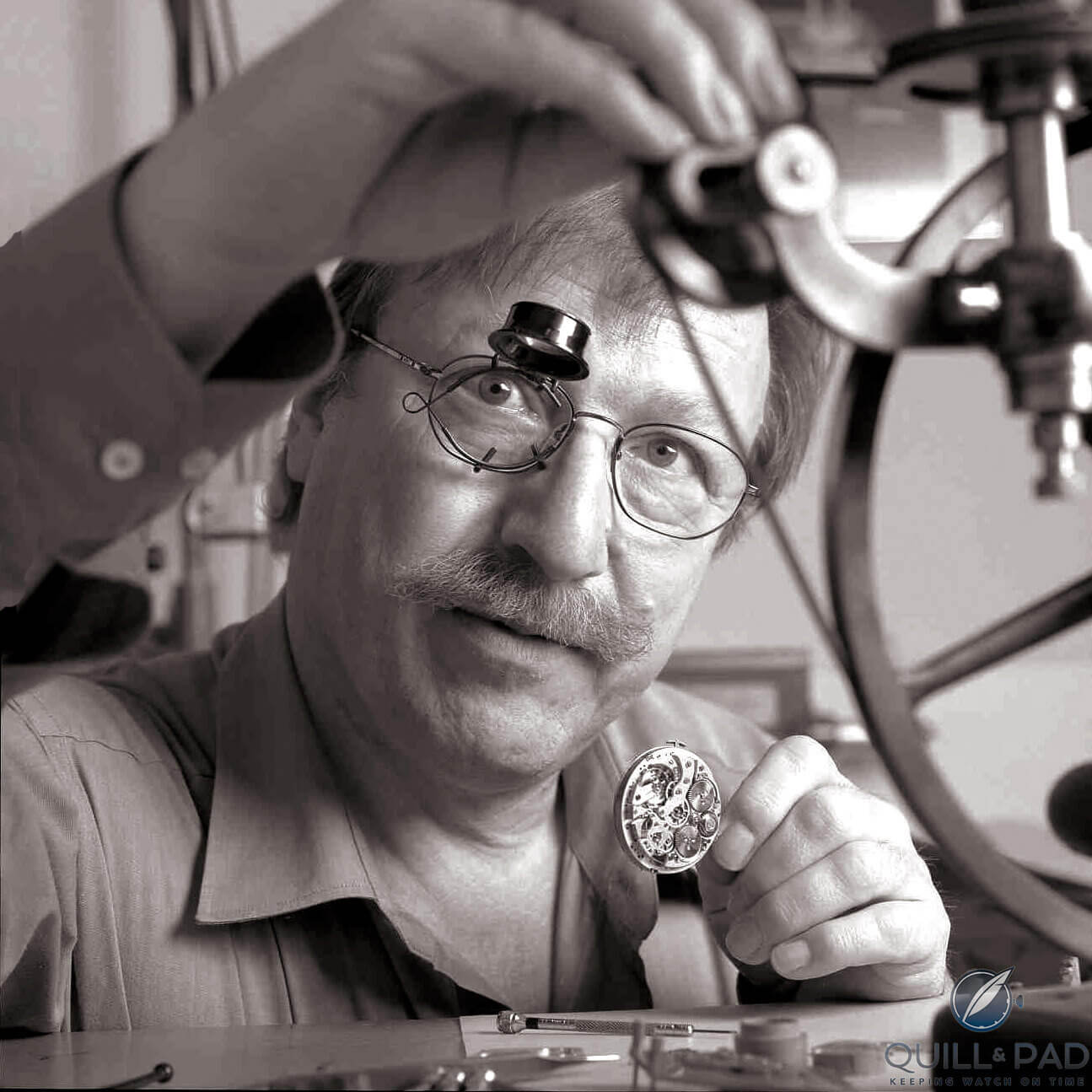

In his day-to-day life, this energy turns into an ability to motivate, to which he attributes his success in building up Swatch Group, in putting the Swiss watch industry back on track and in turning around Breguet, which was in sorry financial shape when he took over in 1999. “When I go to a company, I analyze everything, I am known for this, and I get people motivated, they go voooom! Then you have success.” At Breguet, it additionally took “a great act of balance” to maintain the continuity of tradition and modern technology. He admits to loving art and having an affinity for technology. “At Breguet, we have people with diplomas in electronics, microtechnology and precision engineering, we have watchmakers and we have designers, who are wonderful artists,” he points out. “If you can coordinate them, it’s absolutely fantastic.”

Tomorrow’s world

Hayek’s voice is calm, almost monotonous, but it is obvious that his mind is ticking away like the most complicated watch, producing a fugue-like flow of ideas, the themes arising out of nowhere, by association, intertwining and then moving away again. He slips easily from talking of his delight in astronomy – another aspect of the horological art – to his feelings about mankind… “I never forget that I am a tiny thing on a small planet in a small solar system in a huge universe,” he suddenly intones, without changing rhythm. It’s a topic he returns to often throughout the interview, the fragility of human existence. But the entrepreneurial theme needs space in the conversation, and so with little prompting, he begins describing his newest project: harnessing solar energy and producing hydrogen through electrolysis to run cars and other machines.

“My dream has always been to make a car with photovoltaic cells that channel solar energy into power and to have a reservoir to run a car at least 500 to 700 kilometers without charging it again.” Suddenly, he is back to being the founder of successful businesses, a man of vision, at ease with figures, spread sheets, budgets, bankers, politicians, competitors. He describes concisely and with perfect order how the project has been launched. “I invested in a company called Belenos Clean Power AG, a holding created to accelerate the resources we have to make clean power.” As if endowed with a life of its own, his hand reaches for a ballpoint pen. Meticulously, he draws a chart while at the same time explaining the different joint ventures needed to develop the electrolysis by decentralized systems, the making of the fuel cells, the photovoltaic cells the special batteries needed to store the power. At the bottom of the page, he sketches a car that looks a little like an old Renault Alpine, its roof lined with photovoltaic cells.

Many have tried alternative power sources before, many are still plugging away at it, but when Hayek talks, people listen. His board includes Joseph Ackermann of Deutsche Bank and Ralph Eichler from the ETH in Zurich. Can Switzerland develop an automotive industry? “We are a big financial power,” he points out, “we have no oil companies that can tell our government ‘stop these guys and pass money to research institutes to find something else.’ Thirdly, we do not have an automotive industry saying they have already invested so much in the engines we have developed, if we have to stop we will lose 6,000 jobs. And we have enormous know-how and patent services.” And then his voice drops into a pianissimo, it becomes prayer-like: “What would you do if you were sitting in a spaceship that everyone is trying to destroy, and if that would happen, one of your children would die. You, too, would use your resources…”

Peace is prosperity

He is not a political animal by any means, but a note of sadness enters when he talks about the dismantling of his native Lebanon, today a political football in a bizarre game without referees. But it is not only the tiny Mediterranean country that worries him. “I would hope that people drop violence and respect human rights all over the world. Everyone is criticizing China for Tibet today, but if you look at what the Americans are doing in Guantánamo Bay, I am ashamed of them, my father was American, if you see what Israel is doing with the Palestinians, they take any excuse to fire rockets there, and look at what Russia is doing to Chechnya. That all must stop.”

Nicolas Hayek turned 80 in 2008, and the newspapers, much to his annoyance, played it up with lots of fanfare. His dislike for these types of celebrations is genuine and may have to do with his philosophy of “never doing unnecessary things.” Like going to Hollywood to a party organized by the Cohen brothers to celebrate some film. Ironically, during our interview, a man enters and rather pompously congratulates him on turning “four-score years young.” The suit does not notice the almost reptilian look his kind but grandiloquent words have harvested. “I don’t look backwards,” he says bluntly as soon as the fellow is out of earshot. What does make him proud is the result of a recent poll that suggests he is the most trusted man in Switzerland. It is hardly any wonder. Way before the word sustainability became used and abused, Hayek was living it, making a fortune creating enterprises, value and above all jobs. This differentiates him from the robber barons of our age of quick wealth, the carpetbaggers, the tough-as- nails managers, who bewail having to cut jobs, and pocket the bonuses for doing so. “Don’t ever plan to be rich, because you will never be rich. Plan to help people with things that everybody needs, do these things intelligently, this society will be grateful.” And without warning, he tags on a brief statement that comes out of the blue, an afterthought straight from his depths that says more about him than all of his deeds: “I am a happy man, I was always a happy man; I drink life like somebody who is always thirsty.” Nicolas Hayek is still a young man with a quest in his heart and a twinkle in his eye.

Goodbye, Mr. Hayek.